Kitchener Refugee Camp

Set up as a parallel scheme to the Kindertransport, Kitchener Camp provided a safe haven to 4000 Jewish victims of Nazism

A Refugee Camp In Kent

After Kristallnacht in November 1938, 30,000 Jewish men were taken to concentration camps.

In Britain, the Jewish community persuaded the Government to relax visa restrictions and under the direction of the Central British Fund for Germany Jewry (today’s World Jewish Relief) an abandoned army training camp in Kent was identified to be converted into a refugee camp for these men.

The Lads Brigade

The Jewish Lads Brigade set up and ran the camp, and Brigade stalwarts Jonas May, his brother Phineas and architect Ernest Joseph, took on the daunting task of breathing life into a site that had been neglected for two decades.

A Tiny Town

Its evolution into a tiny town was largely overseen by the resident refugees, providing a level of autonomy and trust that enabled these broken men to regain some equilibrium. Most would never see their families again.

Camp Orchestra

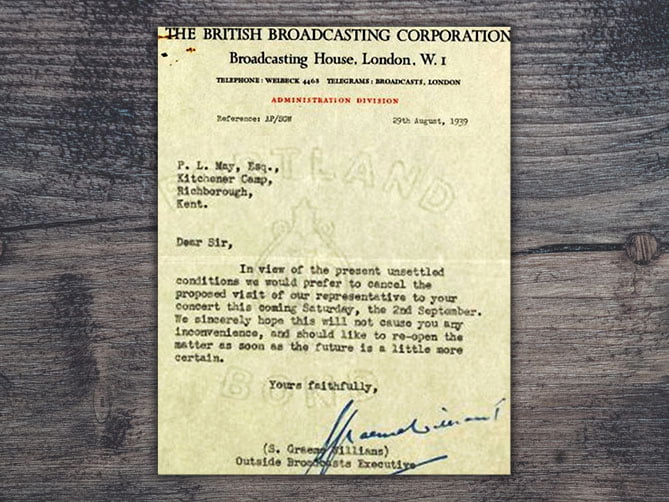

Relations with the locals were warm. Many volunteers offered English tuition and a wide range of practical skills-classes, ndesigned to help the men’s resettlement, were set up. Music became hugely significant and over time, an occasional gathering of refugee instrumental enthusiasts grew into a camp orchestra.

New Beginnings

War ended hopes of being reunited with loved ones. It also scuppered plans with the BBC to broadcast a concert from the camp. Many Kitchener men joined the Pioneer Corp of the British Army, but after the fall of France, in May 1940, along with other refugees in the country, the others were interned on the Isle of Man.

Almost 4000 Jews found refuge at Kitchener Camp. By the end of the war, as the darkest of fears for those they had left behind were so tragically confirmed, the camaraderie of the camp faded. Yet this remarkable act of rescue enabled thousands of new beginnings which, over the generations, have contributed so much to this country.

Leave To Land

Dr Clare Weissenberg is the daughter of Kitchener Camp refugee Werner, and the curator of both the Kitchener Camp Project website and the "Leave to Land" Kitchener camp exhibition .

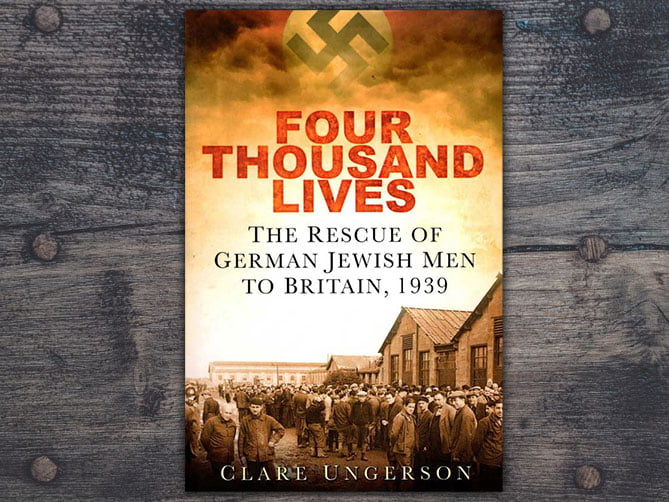

Four Thousand Lives

Professor Clare Ungerson, Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at Southampton University, lives in Sandwich, Kent, and is author of the seminal study on Kitchener Camp, Four Thousand Lives: The rescue of German Jewish men to Britain, 1939. Adrienne Harris and Robert May’s fathers, Jonas and Phineas May, were central to setting up and managing the scheme. Stephen Nelken and Paul Secher and both sons of Kitchener men.

Putting Kitchener Back On The Map

The Kitchener Camp Committee is responsible for bringing the little-known story of Kitchener Camp to public prominence (from left to right Clare Ungerson, Adrienne Harris, Robert May, Clare Weissenberg Stephen Nelken and Paul Secher).